INSIDE SPACE PATROL!

[Comments by Joe Sarno, from SPACE ACADEMY NEWSLETTER #2, (September - October 1978) and #4 (January - February 1979:]

While the quality and quantity of actors was

somewhat suspect, and did not aid in the continuity of the

shows, [SPACE PATROL] did have improving production values

over the years. Costumes were well-designed, and the sets

were spacious AND well-designed. Shows oft-times would have

jungle scenes, complete with mountains to climb and rivers

to cross, and these were obviously indoor sets! Miniatures

were added, including a nice view of the city-surface of the

artificial planet Terra, with rockets landing and taking

off.

In retrospect, the show was not always as imaginative as it

could have been. The plots were typical TV fare of the day,

and the science was oft-times far from accurate. But it was

about all we had! And it was particularly blessed by a

splendid cast of leading characters, played by Ed Kemmer,

Lyn Osborn, Ken Mayer, Virginia Hewitt, Nina Bara and Bela

Kovacs. While the quality and quantity of actors was

somewhat suspect, and did not aid in the continuity of the

shows, [SPACE PATROL] did have improving production values

over the years. Costumes were well-designed, and the sets

were spacious AND well-designed. Shows oft-times would have

jungle scenes, complete with mountains to climb and rivers

to cross, and these were obviously indoor sets! Miniatures

were added, including a nice view of the city-surface of the

artificial planet Terra, with rockets landing and taking

off.

In retrospect, the show was not always as imaginative as it

could have been. The plots were typical TV fare of the day,

and the science was oft-times far from accurate. But it was

about all we had! And it was particularly blessed by a

splendid cast of leading characters, played by Ed Kemmer,

Lyn Osborn, Ken Mayer, Virginia Hewitt, Nina Bara and Bela

Kovacs.

Buzz Corry (Kemmer) was fast to take action, able to

think on his feet and act quickly to save his crewmates from

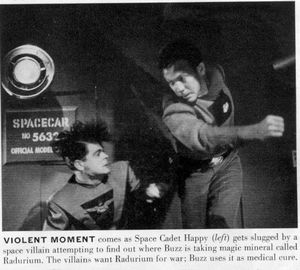

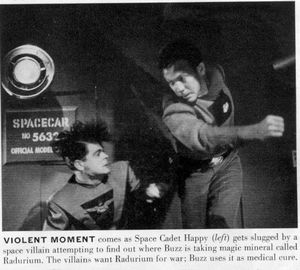

dangerous situations. Cadet Happy (Osborn) was easy-going,

with an inexperienced knack for making the wrong move, but

always reliable in a good fight. Major Robbie Robertson

(Mayer) had a more romantic bent, and though cut in the same

heroic mold as Buzz, he seemed more introspective, more

likely to question his decisions, worrying of the

consequences of his actions. Tonga (Bara) and Carol

(Hewitt) were unique among the early kid space shows.

Definitely an attempt to draw a more adult audience by

presenting a bit of cheesecake on the show, they exuded sex,

and while definitely of the weaker sex, they were often the

center of the show [even if merely] being captured by

villains and rescued by the heroes. They were depicted as

quite a bit different than the typical heroines of their

day; they had brains, each [being credited with] having made

important scientific contributions [to Space Patrol

technology] during the course of the show's run on TV.

[Comments from THE GREAT TELEVISON HEROES by Don Glut and Jim Harmon, Doubleday, NY, 1975:]

A particular story line on SPACE PATROL makes one almost

believe that the [writer was] having lunch with the writers

of CAPTAIN VIDEO (even though SPACE PATROL was telecast from

Hollywood and VIDEO from New York). While Video was

battling Tobor the robot, Commander Corry was troubled by a

mechanical man called Five. Like Tobor, Five was controlled

by an evil woman, and was impervious even to the ray guns of

the Space Patrol. But unlike Tobor, Five [appeared to be

just a man], wearing fatigues and with a dark, artificial

face. (When it came to robots, CAPTAIN VIDEO spared more of

its budget.)

Tobor was destroyed on a Friday. The very next morning,

Commander Corry devised a way to destroy Five. The robot

stalked toward him like the Frankenstein Monster. There was

nothing left for Buzz to do but test out the device he'd

been working on in his spare time. Buzz [whipped out] his

pocket-size invention that changed his voice to the same

wavelength [used by] Five's mistress and began shouting

contradictory orders. Five exploded with a puff of smoke

set off by the special effects men. [Alas,] to viewers who

had seen CAPTAIN VIDEO the night before, the [technique used

to destroy] Five the robot was nothing new!

From CHILDRENS' TELEVISION--- THE FIRST 35 YEARS, 1946-81, by George W. Woolery (Scarecrow Press, 1983):]

Telecast live from a remodeled sound stage at Vitagraph

Studios, purchased in 1949 for ABC's Hollywood facilities,

the series benefitted from skilled technicians, rebuilt

movie sets, large spaceship mockups, and plenty of room for

the spacemen to move around. Buzz Corry (Kemmer) was fast to take action, able to

think on his feet and act quickly to save his crewmates from

dangerous situations. Cadet Happy (Osborn) was easy-going,

with an inexperienced knack for making the wrong move, but

always reliable in a good fight. Major Robbie Robertson

(Mayer) had a more romantic bent, and though cut in the same

heroic mold as Buzz, he seemed more introspective, more

likely to question his decisions, worrying of the

consequences of his actions. Tonga (Bara) and Carol

(Hewitt) were unique among the early kid space shows.

Definitely an attempt to draw a more adult audience by

presenting a bit of cheesecake on the show, they exuded sex,

and while definitely of the weaker sex, they were often the

center of the show [even if merely] being captured by

villains and rescued by the heroes. They were depicted as

quite a bit different than the typical heroines of their

day; they had brains, each [being credited with] having made

important scientific contributions [to Space Patrol

technology] during the course of the show's run on TV.

[Comments from THE GREAT TELEVISON HEROES by Don Glut and Jim Harmon, Doubleday, NY, 1975:]

A particular story line on SPACE PATROL makes one almost

believe that the [writer was] having lunch with the writers

of CAPTAIN VIDEO (even though SPACE PATROL was telecast from

Hollywood and VIDEO from New York). While Video was

battling Tobor the robot, Commander Corry was troubled by a

mechanical man called Five. Like Tobor, Five was controlled

by an evil woman, and was impervious even to the ray guns of

the Space Patrol. But unlike Tobor, Five [appeared to be

just a man], wearing fatigues and with a dark, artificial

face. (When it came to robots, CAPTAIN VIDEO spared more of

its budget.)

Tobor was destroyed on a Friday. The very next morning,

Commander Corry devised a way to destroy Five. The robot

stalked toward him like the Frankenstein Monster. There was

nothing left for Buzz to do but test out the device he'd

been working on in his spare time. Buzz [whipped out] his

pocket-size invention that changed his voice to the same

wavelength [used by] Five's mistress and began shouting

contradictory orders. Five exploded with a puff of smoke

set off by the special effects men. [Alas,] to viewers who

had seen CAPTAIN VIDEO the night before, the [technique used

to destroy] Five the robot was nothing new!

From CHILDRENS' TELEVISION--- THE FIRST 35 YEARS, 1946-81, by George W. Woolery (Scarecrow Press, 1983):]

Telecast live from a remodeled sound stage at Vitagraph

Studios, purchased in 1949 for ABC's Hollywood facilities,

the series benefitted from skilled technicians, rebuilt

movie sets, large spaceship mockups, and plenty of room for

the spacemen to move around.

Ten days before they were to graduate from

the Pasadena Playhouse, [Producer Mike] Moser signed two

aspiring young thespians for the principal roles. They were

veterans, fliers in the Second World War who had some

knowledge of vanquishing villains in the wild blue yonder,

if not in outer space. Ed Kemmer was a real-life flying

hero from Reading, PA, who crashed on his forty-eighth

mission over Germany and developed an interest in acting

while imprisoned in a Nazi Stalag. Detroit-born Clois Lyn

Osborn (who died at age 36 after brain surgery in 1958) was

a former U.S. Navy radioman and gunner.

[From an interview with Ed Kemmer in SATURDAY MORNING TV by Gary Grossman (Dell, 1981):] Ten days before they were to graduate from

the Pasadena Playhouse, [Producer Mike] Moser signed two

aspiring young thespians for the principal roles. They were

veterans, fliers in the Second World War who had some

knowledge of vanquishing villains in the wild blue yonder,

if not in outer space. Ed Kemmer was a real-life flying

hero from Reading, PA, who crashed on his forty-eighth

mission over Germany and developed an interest in acting

while imprisoned in a Nazi Stalag. Detroit-born Clois Lyn

Osborn (who died at age 36 after brain surgery in 1958) was

a former U.S. Navy radioman and gunner.

[From an interview with Ed Kemmer in SATURDAY MORNING TV by Gary Grossman (Dell, 1981):]

We all worked our butts off on SPACE PATROL. It was

a struggle just to come up with a plot and learn the lines

and get it on the air. We'd find out on the air that we

were 5 minutes too long, so we'd jump on each other's lines

and cut the show. It's a pressure we didn't need. You [get

it done,] but you pay a price in production, lighting and

performance.... We prayed for the weekday show to [get

cancelled], because it was just too much.

[On live TV, the rule is... things go wrong.] I remember we

encountered a tribe of Amazons. I think they hired all the

tall girls in Hollywood for [these] episode[s]. [The

Amazons] captured [Happy and me] and tied us to a tree, and

one aimed a crossbow at me. [The effects team had said,]

"Don't worry [about accidents], the string that throws the

arrow is a very weak rubber band, so it won't go more than

two feet." Well, during the show, [an Amazon's] arrow went

sailing. It didn't hit my head. It landed about three feet

directly below!

You can't believe the [demands of] the sponsors. They

wanted Lyn and me to eat their cereal or make [chocolate

milk] right after a fight scene. We could be up in the

rafters of the studio catwalk and have to rush down,

sometimes with real blood on our faces from a [punch] that

connected. We'd be out of breath, totally exhausted, dirty

from the fight, and [yet we had only seconds to get ready]

to do the commercial.

[From ROARING ROCKETS (9/99):]

I'm sure it is quite unfair to judge SPACE PATROL with the

eyes of a cynical 50-year-old, but in my case it's necessary

because it was not until about 1987 (when I was 48) that I

saw any complete SPACE PATROL programs, courtesy of

videotapes of surviving kinescopes. In the past decade,

I've probably been able to watch about 50 programs in the

series, in this way.

Here's what I think: the real stars of SPACE PATROL are art

directors and set designers Carl Macauley and Seymore Klate.

The sets in which the action takes place are incredibly

spacious and elaborate by 1950s live TV standards, and

amazingly realistic. The studio must have been enormous.

In still photos I've seen of studio exterior and interior,

and in episodes in the "Mr. Proteus" storyline which use

nearly the entire studio itself as a set, doubling for a

factory warehouse, it in fact looks enormous. As the quote

from Woolery indicates above, it was a Hollywood sound

stage. Yet the Macaulay-Klate sets also often use forced

perspective very convincingly to give vast depth to sets

already quite large. In the program "Errand of Mercy" most

of the action takes place inside and outside a very

realistic French countryside farmhouse during WWII. The

camera moves fluidly from room to room, and when Corry,

Happy and Tonga are imprisoned by Nazis in a basement, a

shell-burst blows a hole in the exterior wall and they

emerge in real time through the hole into the night-shrouded

countryside, with further scenes playing out around the

exterior. One certainly gets the illusion of seeing all

sides of the farm house, which in fact is even seen isolated

on a hilltop, with the camera following Happy and Buzz

toward it from the Terra V, in a continuous shot that brings

us to the actual full size set... no miniatures, no forced

perspective! To avoid an impossibly huge backdrop for this

immense set, the action was of course set at night.

The sheer size of the sets could sometimes work against the

actors. In another episode, an office building set is so

large that Ed Kemmer doesn't manage to make it around to the

distant door, from which he is obviouly supposed to emerge

as soon as the scene begins, for many agonizing seconds

after the camera's red light comes on, so that for that

entire time the camera looks at a silent, empty (and

uninteresting) corridor set.

Sets aside, the broadcasts are hampered by relatively feeble

scripts which invite self-parody. Ed Kemmer, a fine actor,

plays the key role of Buzz Corry absolutely straight, and he

is entirely convincing, no matter how absurd may be the

antics the script entangles him in. Lyn Osborn is saddled

with a poorly written comical-sidekick role, but plays

straight where it counts. Ken Mayer, Virginia Hewitt and

(in earlier shows) Nina Bara take their cues from Kemmer, so

that the human aspect of the adventures is always

believable, no matter how unsatisfactory the plot,

pseudoscientific gimmick, action or dialogue. While the

scripts don't depict any actual romantic attachments between

Corry and Carol, or Robbie and Tonga, the actors partly fill

in the blanks, with Carol becoming tremendously agitated,

often near hysteria, when Buzz is in danger, and Robbie

becoming frantic when Tonga fails to check in on schedule.

The physical stamina of Ed Kemmer is incredible, and it's a

good thing, because the poorly-planned scripts and direction

often require him to engage in an extended, violent physical

stunt, and then immediately to run from one set to another,

sometimes while frantically changing costume, and still

deliver dialogue at the beginning of the new sequence. You

can often see him fighting to regularize his breathing when

he first appears on set, but the astonishing thing is that

it usually takes him only a few seconds to regain normal

respiration. The need to do live commercials only added to

his already acute woes, as he mentions in the interview

quoted in part above. It was Kemmer himself who

choreographed the very realistic fist fights and wrestling We all worked our butts off on SPACE PATROL. It was

a struggle just to come up with a plot and learn the lines

and get it on the air. We'd find out on the air that we

were 5 minutes too long, so we'd jump on each other's lines

and cut the show. It's a pressure we didn't need. You [get

it done,] but you pay a price in production, lighting and

performance.... We prayed for the weekday show to [get

cancelled], because it was just too much.

[On live TV, the rule is... things go wrong.] I remember we

encountered a tribe of Amazons. I think they hired all the

tall girls in Hollywood for [these] episode[s]. [The

Amazons] captured [Happy and me] and tied us to a tree, and

one aimed a crossbow at me. [The effects team had said,]

"Don't worry [about accidents], the string that throws the

arrow is a very weak rubber band, so it won't go more than

two feet." Well, during the show, [an Amazon's] arrow went

sailing. It didn't hit my head. It landed about three feet

directly below!

You can't believe the [demands of] the sponsors. They

wanted Lyn and me to eat their cereal or make [chocolate

milk] right after a fight scene. We could be up in the

rafters of the studio catwalk and have to rush down,

sometimes with real blood on our faces from a [punch] that

connected. We'd be out of breath, totally exhausted, dirty

from the fight, and [yet we had only seconds to get ready]

to do the commercial.

[From ROARING ROCKETS (9/99):]

I'm sure it is quite unfair to judge SPACE PATROL with the

eyes of a cynical 50-year-old, but in my case it's necessary

because it was not until about 1987 (when I was 48) that I

saw any complete SPACE PATROL programs, courtesy of

videotapes of surviving kinescopes. In the past decade,

I've probably been able to watch about 50 programs in the

series, in this way.

Here's what I think: the real stars of SPACE PATROL are art

directors and set designers Carl Macauley and Seymore Klate.

The sets in which the action takes place are incredibly

spacious and elaborate by 1950s live TV standards, and

amazingly realistic. The studio must have been enormous.

In still photos I've seen of studio exterior and interior,

and in episodes in the "Mr. Proteus" storyline which use

nearly the entire studio itself as a set, doubling for a

factory warehouse, it in fact looks enormous. As the quote

from Woolery indicates above, it was a Hollywood sound

stage. Yet the Macaulay-Klate sets also often use forced

perspective very convincingly to give vast depth to sets

already quite large. In the program "Errand of Mercy" most

of the action takes place inside and outside a very

realistic French countryside farmhouse during WWII. The

camera moves fluidly from room to room, and when Corry,

Happy and Tonga are imprisoned by Nazis in a basement, a

shell-burst blows a hole in the exterior wall and they

emerge in real time through the hole into the night-shrouded

countryside, with further scenes playing out around the

exterior. One certainly gets the illusion of seeing all

sides of the farm house, which in fact is even seen isolated

on a hilltop, with the camera following Happy and Buzz

toward it from the Terra V, in a continuous shot that brings

us to the actual full size set... no miniatures, no forced

perspective! To avoid an impossibly huge backdrop for this

immense set, the action was of course set at night.

The sheer size of the sets could sometimes work against the

actors. In another episode, an office building set is so

large that Ed Kemmer doesn't manage to make it around to the

distant door, from which he is obviouly supposed to emerge

as soon as the scene begins, for many agonizing seconds

after the camera's red light comes on, so that for that

entire time the camera looks at a silent, empty (and

uninteresting) corridor set.

Sets aside, the broadcasts are hampered by relatively feeble

scripts which invite self-parody. Ed Kemmer, a fine actor,

plays the key role of Buzz Corry absolutely straight, and he

is entirely convincing, no matter how absurd may be the

antics the script entangles him in. Lyn Osborn is saddled

with a poorly written comical-sidekick role, but plays

straight where it counts. Ken Mayer, Virginia Hewitt and

(in earlier shows) Nina Bara take their cues from Kemmer, so

that the human aspect of the adventures is always

believable, no matter how unsatisfactory the plot,

pseudoscientific gimmick, action or dialogue. While the

scripts don't depict any actual romantic attachments between

Corry and Carol, or Robbie and Tonga, the actors partly fill

in the blanks, with Carol becoming tremendously agitated,

often near hysteria, when Buzz is in danger, and Robbie

becoming frantic when Tonga fails to check in on schedule.

The physical stamina of Ed Kemmer is incredible, and it's a

good thing, because the poorly-planned scripts and direction

often require him to engage in an extended, violent physical

stunt, and then immediately to run from one set to another,

sometimes while frantically changing costume, and still

deliver dialogue at the beginning of the new sequence. You

can often see him fighting to regularize his breathing when

he first appears on set, but the astonishing thing is that

it usually takes him only a few seconds to regain normal

respiration. The need to do live commercials only added to

his already acute woes, as he mentions in the interview

quoted in part above. It was Kemmer himself who

choreographed the very realistic fist fights and wrestling

matches that frequently climaxed Corry's

adventures, as he subdued the bad guy with bare hands. It's

noteworthy that he rarely spares himself in these sequences.

The fights go on for unexpectedly long times, and involve

continuous, extreme physical exertion. He always gives the

kids a "payoff" for their faithful viewing, even though he

himself pays the full price in the next scene, having to hit

his mark and remember and deliver dialogue while completely

exhausted.

Another thing that hampers the program is a lack of

colorful, scenery-chewing villains. CAPTAIN VIDEO's

impressive parade of bad guys drew on an inexhaustible

supply of Broadway character actors, whose broad "hammy"

stage techniques make their villains memorable, and always

exciting to watch. But SPACE PATROL's parade of bad guys is

drawn from an inexhaustible supply of Hollywood character

actors, whose subdued cinema acting styles make their

villains completely forgettable. Who now remembers Major

Gorla, Captain Kronk, Professor Garson, Doctor Phillips,

Major Gruell, the Thormanoids (even though one was played by

Lee Van Cleef), Thorgan, Captain Dagger, Agent X, Dr. Kurt,

Letha, Gart Stanger, Ahyo, Arachna, Raymo and Ula...? Only

Bela Kovacs as the Black Falcon, Prince Baccarratti, makes

any significant impression... a fact well appreciated by the

program's creators, who use Baccarratti over and over, in

adventure after adventure. Marvin Miller is also quite good

as Mr. Proteus.

As the extract from THE GREAT TELEVISION HEROES indicates,

the sole, overworked writer for the 30 minute weekend SPACE

PATROL shows was driven perilously close to plagiarism,

although it was almost always self-plagiarism. Far too many

SPACE PATROL episodes were carbon copies of previous

episodes, with setting and name of villain changed. SPACE

PATROL would have benefitted greatly from a wide stable of

regular writers, such as CAPTAIN VIDEO and SPACE CADET

enjoyed.

In selecting comments for this page, I have not omitted any

positive remarks. I had great trouble finding ANYTHING in

print that was not generally negative in tone. Yet many

kids who watched the program regularly during 1950-55 have

the fondest possible memories of it, even half a century

later. I think it is fair to say that while SPACE PATROL

lacks the realistic human dimension of TOM CORBETT, SPACE

CADET, or the imagination and color of CAPTAIN VIDEO, it

partially makes up for these lacks in sheer heroics and

spectacle. matches that frequently climaxed Corry's

adventures, as he subdued the bad guy with bare hands. It's

noteworthy that he rarely spares himself in these sequences.

The fights go on for unexpectedly long times, and involve

continuous, extreme physical exertion. He always gives the

kids a "payoff" for their faithful viewing, even though he

himself pays the full price in the next scene, having to hit

his mark and remember and deliver dialogue while completely

exhausted.

Another thing that hampers the program is a lack of

colorful, scenery-chewing villains. CAPTAIN VIDEO's

impressive parade of bad guys drew on an inexhaustible

supply of Broadway character actors, whose broad "hammy"

stage techniques make their villains memorable, and always

exciting to watch. But SPACE PATROL's parade of bad guys is

drawn from an inexhaustible supply of Hollywood character

actors, whose subdued cinema acting styles make their

villains completely forgettable. Who now remembers Major

Gorla, Captain Kronk, Professor Garson, Doctor Phillips,

Major Gruell, the Thormanoids (even though one was played by

Lee Van Cleef), Thorgan, Captain Dagger, Agent X, Dr. Kurt,

Letha, Gart Stanger, Ahyo, Arachna, Raymo and Ula...? Only

Bela Kovacs as the Black Falcon, Prince Baccarratti, makes

any significant impression... a fact well appreciated by the

program's creators, who use Baccarratti over and over, in

adventure after adventure. Marvin Miller is also quite good

as Mr. Proteus.

As the extract from THE GREAT TELEVISION HEROES indicates,

the sole, overworked writer for the 30 minute weekend SPACE

PATROL shows was driven perilously close to plagiarism,

although it was almost always self-plagiarism. Far too many

SPACE PATROL episodes were carbon copies of previous

episodes, with setting and name of villain changed. SPACE

PATROL would have benefitted greatly from a wide stable of

regular writers, such as CAPTAIN VIDEO and SPACE CADET

enjoyed.

In selecting comments for this page, I have not omitted any

positive remarks. I had great trouble finding ANYTHING in

print that was not generally negative in tone. Yet many

kids who watched the program regularly during 1950-55 have

the fondest possible memories of it, even half a century

later. I think it is fair to say that while SPACE PATROL

lacks the realistic human dimension of TOM CORBETT, SPACE

CADET, or the imagination and color of CAPTAIN VIDEO, it

partially makes up for these lacks in sheer heroics and

spectacle.

|

|

[From Elliot Swanson(9/99):]

I might add that a key reason this program remains a

stronger presence than many of the other competing space

operas of the early 1950s--even those that were better

written and funded--is the strong and frequent integration

of the toys/premiums offered in the advertisements with the

props used in the show's adventures. You could buy and own

many of the objects used by Corry and Happy, and somehow

this created a powerful psychological link to that imaginary

world... like carrying an object out of a dream. And it's

one of the reasons that the Space Patrol premiums and toys

command such extraordinary prices today on the collectors'

market. In Space Patrol, the confluence of marketing with

what one saw on the television screen made for one of the

most incredible connections to an imaginary world that has

ever existed, and I know of no other television show that

did it to this degree. And it's further reinforced by Space

Patrol's dream-like noir atmosphere, that the low budgets

mandated--- to keep you from seeing the sets too well. As

with radio, there were a lot of dark, empty places for one's

imagination to fill in.

Return to SPACE PATROL.

Return to SPACE PATROL.

|

While the quality and quantity of actors was

somewhat suspect, and did not aid in the continuity of the

shows, [SPACE PATROL] did have improving production values

over the years. Costumes were well-designed, and the sets

were spacious AND well-designed. Shows oft-times would have

jungle scenes, complete with mountains to climb and rivers

to cross, and these were obviously indoor sets! Miniatures

were added, including a nice view of the city-surface of the

artificial planet Terra, with rockets landing and taking

off.

In retrospect, the show was not always as imaginative as it

could have been. The plots were typical TV fare of the day,

and the science was oft-times far from accurate. But it was

about all we had! And it was particularly blessed by a

splendid cast of leading characters, played by Ed Kemmer,

Lyn Osborn, Ken Mayer, Virginia Hewitt, Nina Bara and Bela

Kovacs.

While the quality and quantity of actors was

somewhat suspect, and did not aid in the continuity of the

shows, [SPACE PATROL] did have improving production values

over the years. Costumes were well-designed, and the sets

were spacious AND well-designed. Shows oft-times would have

jungle scenes, complete with mountains to climb and rivers

to cross, and these were obviously indoor sets! Miniatures

were added, including a nice view of the city-surface of the

artificial planet Terra, with rockets landing and taking

off.

In retrospect, the show was not always as imaginative as it

could have been. The plots were typical TV fare of the day,

and the science was oft-times far from accurate. But it was

about all we had! And it was particularly blessed by a

splendid cast of leading characters, played by Ed Kemmer,

Lyn Osborn, Ken Mayer, Virginia Hewitt, Nina Bara and Bela

Kovacs.

Buzz Corry (Kemmer) was fast to take action, able to

think on his feet and act quickly to save his crewmates from

dangerous situations. Cadet Happy (Osborn) was easy-going,

with an inexperienced knack for making the wrong move, but

always reliable in a good fight. Major Robbie Robertson

(Mayer) had a more romantic bent, and though cut in the same

heroic mold as Buzz, he seemed more introspective, more

likely to question his decisions, worrying of the

consequences of his actions. Tonga (Bara) and Carol

(Hewitt) were unique among the early kid space shows.

Definitely an attempt to draw a more adult audience by

presenting a bit of cheesecake on the show, they exuded sex,

and while definitely of the weaker sex, they were often the

center of the show [even if merely] being captured by

villains and rescued by the heroes. They were depicted as

quite a bit different than the typical heroines of their

day; they had brains, each [being credited with] having made

important scientific contributions [to Space Patrol

technology] during the course of the show's run on TV.

[Comments from THE GREAT TELEVISON HEROES by Don Glut and Jim Harmon, Doubleday, NY, 1975:]

A particular story line on SPACE PATROL makes one almost

believe that the [writer was] having lunch with the writers

of CAPTAIN VIDEO (even though SPACE PATROL was telecast from

Hollywood and VIDEO from New York). While Video was

battling Tobor the robot, Commander Corry was troubled by a

mechanical man called Five. Like Tobor, Five was controlled

by an evil woman, and was impervious even to the ray guns of

the Space Patrol. But unlike Tobor, Five [appeared to be

just a man], wearing fatigues and with a dark, artificial

face. (When it came to robots, CAPTAIN VIDEO spared more of

its budget.)

Tobor was destroyed on a Friday. The very next morning,

Commander Corry devised a way to destroy Five. The robot

stalked toward him like the Frankenstein Monster. There was

nothing left for Buzz to do but test out the device he'd

been working on in his spare time. Buzz [whipped out] his

pocket-size invention that changed his voice to the same

wavelength [used by] Five's mistress and began shouting

contradictory orders. Five exploded with a puff of smoke

set off by the special effects men. [Alas,] to viewers who

had seen CAPTAIN VIDEO the night before, the [technique used

to destroy] Five the robot was nothing new!

From CHILDRENS' TELEVISION--- THE FIRST 35 YEARS, 1946-81, by George W. Woolery (Scarecrow Press, 1983):]

Telecast live from a remodeled sound stage at Vitagraph

Studios, purchased in 1949 for ABC's Hollywood facilities,

the series benefitted from skilled technicians, rebuilt

movie sets, large spaceship mockups, and plenty of room for

the spacemen to move around.

Buzz Corry (Kemmer) was fast to take action, able to

think on his feet and act quickly to save his crewmates from

dangerous situations. Cadet Happy (Osborn) was easy-going,

with an inexperienced knack for making the wrong move, but

always reliable in a good fight. Major Robbie Robertson

(Mayer) had a more romantic bent, and though cut in the same

heroic mold as Buzz, he seemed more introspective, more

likely to question his decisions, worrying of the

consequences of his actions. Tonga (Bara) and Carol

(Hewitt) were unique among the early kid space shows.

Definitely an attempt to draw a more adult audience by

presenting a bit of cheesecake on the show, they exuded sex,

and while definitely of the weaker sex, they were often the

center of the show [even if merely] being captured by

villains and rescued by the heroes. They were depicted as

quite a bit different than the typical heroines of their

day; they had brains, each [being credited with] having made

important scientific contributions [to Space Patrol

technology] during the course of the show's run on TV.

[Comments from THE GREAT TELEVISON HEROES by Don Glut and Jim Harmon, Doubleday, NY, 1975:]

A particular story line on SPACE PATROL makes one almost

believe that the [writer was] having lunch with the writers

of CAPTAIN VIDEO (even though SPACE PATROL was telecast from

Hollywood and VIDEO from New York). While Video was

battling Tobor the robot, Commander Corry was troubled by a

mechanical man called Five. Like Tobor, Five was controlled

by an evil woman, and was impervious even to the ray guns of

the Space Patrol. But unlike Tobor, Five [appeared to be

just a man], wearing fatigues and with a dark, artificial

face. (When it came to robots, CAPTAIN VIDEO spared more of

its budget.)

Tobor was destroyed on a Friday. The very next morning,

Commander Corry devised a way to destroy Five. The robot

stalked toward him like the Frankenstein Monster. There was

nothing left for Buzz to do but test out the device he'd

been working on in his spare time. Buzz [whipped out] his

pocket-size invention that changed his voice to the same

wavelength [used by] Five's mistress and began shouting

contradictory orders. Five exploded with a puff of smoke

set off by the special effects men. [Alas,] to viewers who

had seen CAPTAIN VIDEO the night before, the [technique used

to destroy] Five the robot was nothing new!

From CHILDRENS' TELEVISION--- THE FIRST 35 YEARS, 1946-81, by George W. Woolery (Scarecrow Press, 1983):]

Telecast live from a remodeled sound stage at Vitagraph

Studios, purchased in 1949 for ABC's Hollywood facilities,

the series benefitted from skilled technicians, rebuilt

movie sets, large spaceship mockups, and plenty of room for

the spacemen to move around.

Ten days before they were to graduate from

the Pasadena Playhouse, [Producer Mike] Moser signed two

aspiring young thespians for the principal roles. They were

veterans, fliers in the Second World War who had some

knowledge of vanquishing villains in the wild blue yonder,

if not in outer space. Ed Kemmer was a real-life flying

hero from Reading, PA, who crashed on his forty-eighth

mission over Germany and developed an interest in acting

while imprisoned in a Nazi Stalag. Detroit-born Clois Lyn

Osborn (who died at age 36 after brain surgery in 1958) was

a former U.S. Navy radioman and gunner.

[From an interview with Ed Kemmer in SATURDAY MORNING TV by Gary Grossman (Dell, 1981):]

Ten days before they were to graduate from

the Pasadena Playhouse, [Producer Mike] Moser signed two

aspiring young thespians for the principal roles. They were

veterans, fliers in the Second World War who had some

knowledge of vanquishing villains in the wild blue yonder,

if not in outer space. Ed Kemmer was a real-life flying

hero from Reading, PA, who crashed on his forty-eighth

mission over Germany and developed an interest in acting

while imprisoned in a Nazi Stalag. Detroit-born Clois Lyn

Osborn (who died at age 36 after brain surgery in 1958) was

a former U.S. Navy radioman and gunner.

[From an interview with Ed Kemmer in SATURDAY MORNING TV by Gary Grossman (Dell, 1981):]

We all worked our butts off on SPACE PATROL. It was

a struggle just to come up with a plot and learn the lines

and get it on the air. We'd find out on the air that we

were 5 minutes too long, so we'd jump on each other's lines

and cut the show. It's a pressure we didn't need. You [get

it done,] but you pay a price in production, lighting and

performance.... We prayed for the weekday show to [get

cancelled], because it was just too much.

[On live TV, the rule is... things go wrong.] I remember we

encountered a tribe of Amazons. I think they hired all the

tall girls in Hollywood for [these] episode[s]. [The

Amazons] captured [Happy and me] and tied us to a tree, and

one aimed a crossbow at me. [The effects team had said,]

"Don't worry [about accidents], the string that throws the

arrow is a very weak rubber band, so it won't go more than

two feet." Well, during the show, [an Amazon's] arrow went

sailing. It didn't hit my head. It landed about three feet

directly below!

You can't believe the [demands of] the sponsors. They

wanted Lyn and me to eat their cereal or make [chocolate

milk] right after a fight scene. We could be up in the

rafters of the studio catwalk and have to rush down,

sometimes with real blood on our faces from a [punch] that

connected. We'd be out of breath, totally exhausted, dirty

from the fight, and [yet we had only seconds to get ready]

to do the commercial.

[From ROARING ROCKETS (9/99):]

I'm sure it is quite unfair to judge SPACE PATROL with the

eyes of a cynical 50-year-old, but in my case it's necessary

because it was not until about 1987 (when I was 48) that I

saw any complete SPACE PATROL programs, courtesy of

videotapes of surviving kinescopes. In the past decade,

I've probably been able to watch about 50 programs in the

series, in this way.

Here's what I think: the real stars of SPACE PATROL are art

directors and set designers Carl Macauley and Seymore Klate.

The sets in which the action takes place are incredibly

spacious and elaborate by 1950s live TV standards, and

amazingly realistic. The studio must have been enormous.

In still photos I've seen of studio exterior and interior,

and in episodes in the "Mr. Proteus" storyline which use

nearly the entire studio itself as a set, doubling for a

factory warehouse, it in fact looks enormous. As the quote

from Woolery indicates above, it was a Hollywood sound

stage. Yet the Macaulay-Klate sets also often use forced

perspective very convincingly to give vast depth to sets

already quite large. In the program "Errand of Mercy" most

of the action takes place inside and outside a very

realistic French countryside farmhouse during WWII. The

camera moves fluidly from room to room, and when Corry,

Happy and Tonga are imprisoned by Nazis in a basement, a

shell-burst blows a hole in the exterior wall and they

emerge in real time through the hole into the night-shrouded

countryside, with further scenes playing out around the

exterior. One certainly gets the illusion of seeing all

sides of the farm house, which in fact is even seen isolated

on a hilltop, with the camera following Happy and Buzz

toward it from the Terra V, in a continuous shot that brings

us to the actual full size set... no miniatures, no forced

perspective! To avoid an impossibly huge backdrop for this

immense set, the action was of course set at night.

The sheer size of the sets could sometimes work against the

actors. In another episode, an office building set is so

large that Ed Kemmer doesn't manage to make it around to the

distant door, from which he is obviouly supposed to emerge

as soon as the scene begins, for many agonizing seconds

after the camera's red light comes on, so that for that

entire time the camera looks at a silent, empty (and

uninteresting) corridor set.

Sets aside, the broadcasts are hampered by relatively feeble

scripts which invite self-parody. Ed Kemmer, a fine actor,

plays the key role of Buzz Corry absolutely straight, and he

is entirely convincing, no matter how absurd may be the

antics the script entangles him in. Lyn Osborn is saddled

with a poorly written comical-sidekick role, but plays

straight where it counts. Ken Mayer, Virginia Hewitt and

(in earlier shows) Nina Bara take their cues from Kemmer, so

that the human aspect of the adventures is always

believable, no matter how unsatisfactory the plot,

pseudoscientific gimmick, action or dialogue. While the

scripts don't depict any actual romantic attachments between

Corry and Carol, or Robbie and Tonga, the actors partly fill

in the blanks, with Carol becoming tremendously agitated,

often near hysteria, when Buzz is in danger, and Robbie

becoming frantic when Tonga fails to check in on schedule.

The physical stamina of Ed Kemmer is incredible, and it's a

good thing, because the poorly-planned scripts and direction

often require him to engage in an extended, violent physical

stunt, and then immediately to run from one set to another,

sometimes while frantically changing costume, and still

deliver dialogue at the beginning of the new sequence. You

can often see him fighting to regularize his breathing when

he first appears on set, but the astonishing thing is that

it usually takes him only a few seconds to regain normal

respiration. The need to do live commercials only added to

his already acute woes, as he mentions in the interview

quoted in part above. It was Kemmer himself who

choreographed the very realistic fist fights and wrestling

We all worked our butts off on SPACE PATROL. It was

a struggle just to come up with a plot and learn the lines

and get it on the air. We'd find out on the air that we

were 5 minutes too long, so we'd jump on each other's lines

and cut the show. It's a pressure we didn't need. You [get

it done,] but you pay a price in production, lighting and

performance.... We prayed for the weekday show to [get

cancelled], because it was just too much.

[On live TV, the rule is... things go wrong.] I remember we

encountered a tribe of Amazons. I think they hired all the

tall girls in Hollywood for [these] episode[s]. [The

Amazons] captured [Happy and me] and tied us to a tree, and

one aimed a crossbow at me. [The effects team had said,]

"Don't worry [about accidents], the string that throws the

arrow is a very weak rubber band, so it won't go more than

two feet." Well, during the show, [an Amazon's] arrow went

sailing. It didn't hit my head. It landed about three feet

directly below!

You can't believe the [demands of] the sponsors. They

wanted Lyn and me to eat their cereal or make [chocolate

milk] right after a fight scene. We could be up in the

rafters of the studio catwalk and have to rush down,

sometimes with real blood on our faces from a [punch] that

connected. We'd be out of breath, totally exhausted, dirty

from the fight, and [yet we had only seconds to get ready]

to do the commercial.

[From ROARING ROCKETS (9/99):]

I'm sure it is quite unfair to judge SPACE PATROL with the

eyes of a cynical 50-year-old, but in my case it's necessary

because it was not until about 1987 (when I was 48) that I

saw any complete SPACE PATROL programs, courtesy of

videotapes of surviving kinescopes. In the past decade,

I've probably been able to watch about 50 programs in the

series, in this way.

Here's what I think: the real stars of SPACE PATROL are art

directors and set designers Carl Macauley and Seymore Klate.

The sets in which the action takes place are incredibly

spacious and elaborate by 1950s live TV standards, and

amazingly realistic. The studio must have been enormous.

In still photos I've seen of studio exterior and interior,

and in episodes in the "Mr. Proteus" storyline which use

nearly the entire studio itself as a set, doubling for a

factory warehouse, it in fact looks enormous. As the quote

from Woolery indicates above, it was a Hollywood sound

stage. Yet the Macaulay-Klate sets also often use forced

perspective very convincingly to give vast depth to sets

already quite large. In the program "Errand of Mercy" most

of the action takes place inside and outside a very

realistic French countryside farmhouse during WWII. The

camera moves fluidly from room to room, and when Corry,

Happy and Tonga are imprisoned by Nazis in a basement, a

shell-burst blows a hole in the exterior wall and they

emerge in real time through the hole into the night-shrouded

countryside, with further scenes playing out around the

exterior. One certainly gets the illusion of seeing all

sides of the farm house, which in fact is even seen isolated

on a hilltop, with the camera following Happy and Buzz

toward it from the Terra V, in a continuous shot that brings

us to the actual full size set... no miniatures, no forced

perspective! To avoid an impossibly huge backdrop for this

immense set, the action was of course set at night.

The sheer size of the sets could sometimes work against the

actors. In another episode, an office building set is so

large that Ed Kemmer doesn't manage to make it around to the

distant door, from which he is obviouly supposed to emerge

as soon as the scene begins, for many agonizing seconds

after the camera's red light comes on, so that for that

entire time the camera looks at a silent, empty (and

uninteresting) corridor set.

Sets aside, the broadcasts are hampered by relatively feeble

scripts which invite self-parody. Ed Kemmer, a fine actor,

plays the key role of Buzz Corry absolutely straight, and he

is entirely convincing, no matter how absurd may be the

antics the script entangles him in. Lyn Osborn is saddled

with a poorly written comical-sidekick role, but plays

straight where it counts. Ken Mayer, Virginia Hewitt and

(in earlier shows) Nina Bara take their cues from Kemmer, so

that the human aspect of the adventures is always

believable, no matter how unsatisfactory the plot,

pseudoscientific gimmick, action or dialogue. While the

scripts don't depict any actual romantic attachments between

Corry and Carol, or Robbie and Tonga, the actors partly fill

in the blanks, with Carol becoming tremendously agitated,

often near hysteria, when Buzz is in danger, and Robbie

becoming frantic when Tonga fails to check in on schedule.

The physical stamina of Ed Kemmer is incredible, and it's a

good thing, because the poorly-planned scripts and direction

often require him to engage in an extended, violent physical

stunt, and then immediately to run from one set to another,

sometimes while frantically changing costume, and still

deliver dialogue at the beginning of the new sequence. You

can often see him fighting to regularize his breathing when

he first appears on set, but the astonishing thing is that

it usually takes him only a few seconds to regain normal

respiration. The need to do live commercials only added to

his already acute woes, as he mentions in the interview

quoted in part above. It was Kemmer himself who

choreographed the very realistic fist fights and wrestling

matches that frequently climaxed Corry's

adventures, as he subdued the bad guy with bare hands. It's

noteworthy that he rarely spares himself in these sequences.

The fights go on for unexpectedly long times, and involve

continuous, extreme physical exertion. He always gives the

kids a "payoff" for their faithful viewing, even though he

himself pays the full price in the next scene, having to hit

his mark and remember and deliver dialogue while completely

exhausted.

Another thing that hampers the program is a lack of

colorful, scenery-chewing villains. CAPTAIN VIDEO's

impressive parade of bad guys drew on an inexhaustible

supply of Broadway character actors, whose broad "hammy"

stage techniques make their villains memorable, and always

exciting to watch. But SPACE PATROL's parade of bad guys is

drawn from an inexhaustible supply of Hollywood character

actors, whose subdued cinema acting styles make their

villains completely forgettable. Who now remembers Major

Gorla, Captain Kronk, Professor Garson, Doctor Phillips,

Major Gruell, the Thormanoids (even though one was played by

Lee Van Cleef), Thorgan, Captain Dagger, Agent X, Dr. Kurt,

Letha, Gart Stanger, Ahyo, Arachna, Raymo and Ula...? Only

Bela Kovacs as the Black Falcon, Prince Baccarratti, makes

any significant impression... a fact well appreciated by the

program's creators, who use Baccarratti over and over, in

adventure after adventure. Marvin Miller is also quite good

as Mr. Proteus.

As the extract from THE GREAT TELEVISION HEROES indicates,

the sole, overworked writer for the 30 minute weekend SPACE

PATROL shows was driven perilously close to plagiarism,

although it was almost always self-plagiarism. Far too many

SPACE PATROL episodes were carbon copies of previous

episodes, with setting and name of villain changed. SPACE

PATROL would have benefitted greatly from a wide stable of

regular writers, such as CAPTAIN VIDEO and SPACE CADET

enjoyed.

In selecting comments for this page, I have not omitted any

positive remarks. I had great trouble finding ANYTHING in

print that was not generally negative in tone. Yet many

kids who watched the program regularly during 1950-55 have

the fondest possible memories of it, even half a century

later. I think it is fair to say that while SPACE PATROL

lacks the realistic human dimension of TOM CORBETT, SPACE

CADET, or the imagination and color of CAPTAIN VIDEO, it

partially makes up for these lacks in sheer heroics and

spectacle.

matches that frequently climaxed Corry's

adventures, as he subdued the bad guy with bare hands. It's

noteworthy that he rarely spares himself in these sequences.

The fights go on for unexpectedly long times, and involve

continuous, extreme physical exertion. He always gives the

kids a "payoff" for their faithful viewing, even though he

himself pays the full price in the next scene, having to hit

his mark and remember and deliver dialogue while completely

exhausted.

Another thing that hampers the program is a lack of

colorful, scenery-chewing villains. CAPTAIN VIDEO's

impressive parade of bad guys drew on an inexhaustible

supply of Broadway character actors, whose broad "hammy"

stage techniques make their villains memorable, and always

exciting to watch. But SPACE PATROL's parade of bad guys is

drawn from an inexhaustible supply of Hollywood character

actors, whose subdued cinema acting styles make their

villains completely forgettable. Who now remembers Major

Gorla, Captain Kronk, Professor Garson, Doctor Phillips,

Major Gruell, the Thormanoids (even though one was played by

Lee Van Cleef), Thorgan, Captain Dagger, Agent X, Dr. Kurt,

Letha, Gart Stanger, Ahyo, Arachna, Raymo and Ula...? Only

Bela Kovacs as the Black Falcon, Prince Baccarratti, makes

any significant impression... a fact well appreciated by the

program's creators, who use Baccarratti over and over, in

adventure after adventure. Marvin Miller is also quite good

as Mr. Proteus.

As the extract from THE GREAT TELEVISION HEROES indicates,

the sole, overworked writer for the 30 minute weekend SPACE

PATROL shows was driven perilously close to plagiarism,

although it was almost always self-plagiarism. Far too many

SPACE PATROL episodes were carbon copies of previous

episodes, with setting and name of villain changed. SPACE

PATROL would have benefitted greatly from a wide stable of

regular writers, such as CAPTAIN VIDEO and SPACE CADET

enjoyed.

In selecting comments for this page, I have not omitted any

positive remarks. I had great trouble finding ANYTHING in

print that was not generally negative in tone. Yet many

kids who watched the program regularly during 1950-55 have

the fondest possible memories of it, even half a century

later. I think it is fair to say that while SPACE PATROL

lacks the realistic human dimension of TOM CORBETT, SPACE

CADET, or the imagination and color of CAPTAIN VIDEO, it

partially makes up for these lacks in sheer heroics and

spectacle.