Space Cadet

Briefing:

Captain Video

More Captain Video

Tom Corbett

More Tom Corbett

Space Patrol

More Space Patrol

Space Hero Files

Video Sources

"I Was There!"

Space Interviews

Space Reports

Space Gallery

Space Album

Space Origins

Space Toy Box

Roaring Plastic

Serial Heroes

The 1950s

Cosmic Feedback

Colliding Heroes

Space Stamps

Roaring Reviews

Roaring Reviews 2!

THE FORGOTTEN NETWORK

DUMONT AND THE BIRTH OF AMERICAN TELEVISION

(Click here for details.) by David Weinstein (Temple University Press, PA, 2004)

Followers of the adventures of CAPTAIN VIDEO and TOM CORBETT, SPACE CADET in the early 1950s necessarily became familiar with the availability (or lack thereof) of DuMont programming in the areas in which they resided. DuMont was at least a player in the struggle to create programming that America's households would tune their newly purchased TVs into, in 1949, but by 1953 they were pretty much licked, and by the spring of 1955 they were out of the picture completely and literally.

Based on Weinstein's

carefully researched and well-organized recounting of the

history of DuMont, it is amazing that the network lasted as

long as it did. The two major networks, NBC and CBS, had

powerful lobbyists who would walk right into the offices of

the FCC or the halls of Congress and unashamedly dictate

regulations or rulings or legislation that openly favored

NBC and CBS, while making it difficult for ABC and

impossible for DuMont to expand. ABC survived by forging

strong ties to Hollywood studios, but an earlier alliance

between DuMont and Paramount was nothing but complete

disaster for DuMont. In fact, just about everything was a

disaster for DuMont... they were even screwed horrendously

by AT&T on coax cable rental fees.

DuMont had no money, but they did have creativity, born of necessity. Director of Programming James Caddigan and a bunch of people often literally hired off the street came up with innovative programming ideas which shaped the direction of all network television programming in the decades to come. Yet even here, DuMont was doomed to lose. Once they had hold of a hot thing, they never had the money to develop it properly, or to retain the performers involved under contract.

Weinstein devotes the first three chapters of this roughly 220-page book to the rise and fall of Allan B. Du Mont as manufacturer and network head. He then turns to the areas in which DuMont's plow first broke the plains, with chapters on daytime TV programming aimed at housewives; on CAPTAIN VIDEO; on DuMont's first successful variety host, Morey Amsterdam; and on its first superstar, Jackie Gleason. Also covered are DuMont's two popular and pioneering police procedural dramas; its surprisingly successful venture into religious programming, with the charismatic and sinister Bishop Fulton J. Sheen; as well as an experiment with late-night programming guided by comic genius Ernie Kovacs.

Often in reading books on TV of the early 1950s one quickly realizes that the author's knowledge of the programs is entirely due to having read a few TV-Guide-type articles on the programs, from that era... in other words, he hasn't a clue. Weinstein, born in 1967, was well aware of this pitfall and he has made an energetic effort to locate and view kinescopes of presumably typical broadcasts of each of the programs he discusses. As a result, he can describe in detail the unique signatures that DuMont's always low budget and often great creativity brought to their successful series.

The book is carefully footnoted, nicely indexed, and professionally bound and printed. Misprints are very few. One of the strangest is the replacement of the word "sight" by "site" in a few inappropriate spots! Recommended to anyone who remembers the heady and heroic days of the Golden Age of Television, or is curious about it.

Against The Grain: MAD Artist Wallace Wood

TwoMorrows, NC, Fall 2003

We didn't know it was the Golden Age. It was early in the 1950s, when Captain Video, Tom Corbett and the other Space Cadets, Buzz Corry, and various imitations adventured through the narrow confines of outer space that would fit on the small TV screens of the day. And at the local movie house, producer George Pal was providing gorgeous-looking technicolor feature films with space travel themes.

But it was in the pages of EC's science fiction comics that an artist who signed himself WOOD was drawing impossibly beautiful women, competent-looking and athletic men in wonderfully complex space suits, and incredible rocket ships that, inside and out, fulfilled and surpassed the wildest dreams of the imaginative youngsters who regularly read the EC lineup. Wood's artwork crammed the small comic-book panels with fantastically detailed architecture, artworks, costumes, animals, plantlife, rocks and machinery. And no comic artist has ever, before or since, created more frighteningly alien space aliens.

When the EC lineup gave birth to a humor comic, MAD, Wood showed

another side. Now his panels, which were often incredibly accurate

simulations of the styles of the artists being parodied, were crammed

with background gags, funny signs and notices, and what seemed like dozens of

tiny, comical characters who stood about viewing the main action.

Wood's detail-rich style is often called his "cluttered" style. And we can see that it existed in even the very earliest panels he drew as a small child; he tried to use every inch of the panel for something. In later years, he claimed to be trying to avoid such "clutter," particularly in a series of superhero comics he created featuring the "T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents." But you still find it, even late in his career, in every bit of work he really, personally cared about, such as THE WORLD OF THE WIZARD KING.

Well, what we have here is a 328 page 8-1/2" by 11" trade paperback crammed with Wood art. Alas, it is also crammed with bland and repetitive text by a variety of contributors. The really awful title is a warning of some really awful writing to be found within. However, every facet of Wood's art career is covered, and there are a number of word-portraits of Wood himself, at work and (rarely) at play, by friends and collaborators. Some of the contributions are worthless, pretentious 350-lb-fanboy crap, like "A Thousand Rays in Your Belly," by Bill Mason. But most explore in some detail some facet of Wood's career as an illustrator, for instance in bubble gum cards, in pulp and digest magazine illustrations, children's book art, advertising art, etc. Of greatest interest, and largely new to me, was the information about Wood's family and early childhood, mainly supplied apparently by his engineer brother. The lack of intelligent editing is continually frustrating. For example, Wood's assistants report spending long hours at the famous Wood "swipe-o-graph"-- but it is never described!

In the film SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE, the young Shakespeare unexpectedly runs into his idol Christopher Marlowe in a tavern. Unable to stop himself, he comes out with a Shakespearian version of that line every creator dreads to hear, "Your old stuff was better." Wood heard this line so often during his roughly 30-year career that it might have fuelled his increasing bitterness and despair as much as his incessant problems with meddling, stupid and crooked editors and publishers did. Everyone who got to know Wood personally was amazed at how repressed he was; he seemed to bottle up everything, aiming at being a kind of drawing machine, capable of producing astonishing work for 20 to 30 hours at a continuous stretch. It ate him up; it ate him alive; poor old Woody! There was not a lot of pleasure in his own life, but oh, boy, how much pleasure he gave to so many kids for so many years. If only you could have known, Woody, how much those kids loved and admired you!

Tom Corbett, Space Cadet Video

Gold Series, Vol. 2, Edge Publishing

We have the first three episodes in the initial "Mercurian Invasion" storyline, from Monday Oct. 2, Wednesday Oct. 4 and Friday Oct. 6, 1950. Tom Corbett's first day at Space Academy (Oct. 2) has been available for years, most recently on a Wade Williams Englewood release, but the two following broadcasts are seen for the first time. In the second broadcast, the Polaris unit is formed and we learn how Roger became the senior cadet. In the third broadcast, we get the priceless first meeting between Dr. Dale and Roger-- of course, not knowing she is a professor, he puts the patented Manning moves on her! Further, Captain Strong is ordered to proceed to Venus on a decoy mission with the Polaris cadets; he and Arkwright intend to dump the cadets safely on Venus while Strong proceeds alone to Mercury to try to make peace with the militant Mercurians. Note that Strong is inexplicably taking off with a rocket crew which has yet to attend a single class at Space Academy! And just as the Polaris takes off, we learn that a Mercurian who stowed away on the scout ship that crashed in episode 1 has sabotaged the Polaris! What a delight to see these "historic" moments again for the first time 53 years after their original telecast! There was a whole month of episodes, 12 in total, in this Mercurian storyline, spanning October 2 to October 27. Four of the episodes have yet to surface.

Frankie Thomas, Al Markim and Jan Merlin have frequently told stories of the scripted "briefing" by Captain Strong, in which the actor (then Michael Harvey) forgot all his lines live on the air, resulting in Harvey being fired. I always assumed this incident occurred in the Friday, October 6 broadcast. But there is no briefing at all in this episode.

The fumble must occur in the still missing Wednesday, October 11 episode, where Strong, on the Polaris control deck, is supposed to fill the cadets in for the first time on their secret mission. At any rate, the next Monday, Harvey was replaced permanently by Ed Bryce.

Next on the tape are three episodes from the 9-episode

"Runaway Asteroid" storyline. What we have are the 2nd

episode in the set, one from about the middle, and the final

episode. I remember seeing only one of these before, the

final episode, where Astro rides an atomic torpedo "Major

King Kong-style" to destroy the asteroid. In the first of

the surviving episodes, Roger, Tom, Astro and Alfie are

surveying asteroids from the surface of one, when a nearby

asteroid explodes and is driven on a collision course to

earth. In the next surviving episode Dr. Dale and Captain

Strong have been sent out in the Rocket Scout Orion to

assist the four cadets, and have burned out a rocket tube on

the Polaris trying to keep up with the runaway asteroid.

This episode features the repairing of the tube, and nice

special effects as Captain Strong drifts away from the ship

and has to be rescued by Tom's toss of a safety line given

some inertia by a tied-on wrench. A bizarre feature of all

the "runaway asteroid" episodes is that the space suits

conspiciously have no oxygen bottles on the back. Why?

The final four episodes are part of the 9-episode ABC 1951

"Alpha Centauri" storyline. The first broadcast is probably

the 2nd in the series, and-- alas!-- is missing about 5

minutes of footage right near the beginning. Tom, Roger,

Alfie and Astro are testing Dr. Dale's new hyperdrive on the

Polaris, when Roger decides to play a prank. Slipping on

magnetic boots, he switches off the "artificial gravity,"

whatever that is, leaving Alfie drifting helpless in the air

of the control deck. Tom enters, rescues Alfie, and enters

into a fistfight with Roger, when Astro storms in to report

that all instruments have just gone dead! All this is

missing from the print (which also has very poor sound). In

the surviving bit of the episode, the cadets try

unsuccessfully to find out what is wrong, while Dr. Dale and

Captain Strong blast off in good old Rocket Scout Orion on a

rescue mission.

The final four episodes are part of the 9-episode ABC 1951

"Alpha Centauri" storyline. The first broadcast is probably

the 2nd in the series, and-- alas!-- is missing about 5

minutes of footage right near the beginning. Tom, Roger,

Alfie and Astro are testing Dr. Dale's new hyperdrive on the

Polaris, when Roger decides to play a prank. Slipping on

magnetic boots, he switches off the "artificial gravity,"

whatever that is, leaving Alfie drifting helpless in the air

of the control deck. Tom enters, rescues Alfie, and enters

into a fistfight with Roger, when Astro storms in to report

that all instruments have just gone dead! All this is

missing from the print (which also has very poor sound). In

the surviving bit of the episode, the cadets try

unsuccessfully to find out what is wrong, while Dr. Dale and

Captain Strong blast off in good old Rocket Scout Orion on a

rescue mission.

The remaining three episodes are from the late middle of the story line and are consecutive. Tom, Roger and Astro are exploring the dense jungles of a planet of Alpha Centauri, when they find themselves cut off from the Polaris by hungry dinosaurs! Captain Strong locates them and orders Dr. Dale and Alfie to take off in the Orion, while Strong tries to get the cadets back to the Polaris. The dinosaurs seen are two small toys and what appears to be a baby alligator with a paper fin on its back. [I remember Al Markim saying he took the alligator home as a pet when its show business career was over.] George Gould's "matting amplifier" is used in many of the sequences, for example as the cadets climb over a dinosaur rendered inert by their paralo-ray guns. [By the way, I did not recognize the props used-- they may be extensively modified Buck Rogers Sonic Ray blasters, but are never shown clearly.]

The matting amplifier gets another workout at the end of the tape, as the cadets and Captain Strong try to cross a river of boiling mud using stepping stones. Amusingly, in the final shot, someone forgets to put the background of boiling mud (actually oatmeal, I assume) into the scene behind the matte of the cadets and stepping stones. Roger naturally steps on the head of some creature lurking in the mud, as the episode ends. These are all great broadcasts, again seen for the first time in 52 years.

All commercials are present, and it is interesting to see them switch from filmed pitches for Kellogg's Corn Flakes ["More Punch 'Til Lunch!"] in the earliest episodes, to live pitches for the Flakes at the beginning of the Alpha Centauri story line, and then to (usually live) pitches for Kellogg's Pep ["The Builder-Upper Wheat Cereal!"] right in the midst of the Alpha Centauri adventure. It is also interesting to see not just Tom, but Roger, Captain Strong, Astro and Commander Arkwright doing the commercials. One commercial in the first of the Alpha Centauri episodes on the tape has the younger brother of Tom Corbett dropping into Commander Arkwright's office, and is actually integrated into the story line as Arkwright explains Tom is off on a mission, and then turns the topic to the wonders of Kellogg's Corn Flakes.

It is also diverting to see how the billing of the cast at the end of each episode varies. The role of Alfie Higgins is identified not by a title card, but by the announcer. In no episode is Margaret (Dr. Dale) Garland credited in any way.

In these episodes Dr. Dale and Captain Strong spend so much time alone on the Rocket Scout Orion, on missions to rescue the four cadets, that one suspects whatever their hinted relationship might have been was physically consummated then, and repeatedly at that! "Ohhhhh, Steve... if only those cadets need rescuing again next week!!!" It is also interesting to see how Dr. Dale's haircut gets shorter and frizzier as the series progresses.

All 10 episodes give us a lot of good old Roger Manning, and plenty of Dr. Dale and Alfie (Alfred P.?) Higgins, in addition to the Tom, Astro and Captain Strong we can always rely on. My understanding is that these are the last remaining kinescopes Swapsale was able to obtain from the estate of Joseph Greene. Get 'em while you can.

Review Comments from Jan Merlin:"[With regard to Astro riding the atomic torpedo, as you hint], I'd like to point out that this incident was copied more than ten years later for the film DR. STRANGELOVE, etcetera, in which Slim Pickens rides an H-bomb to his death. I suspect one of the writers had seen our show!

"As for the paralo-ray guns, as I recall, they were soldering-gun-shaped instruments which we stll see in some shops today. I often broke up a guest heavy in rehearsals by telling him to surrender or I'd solder him to death!"

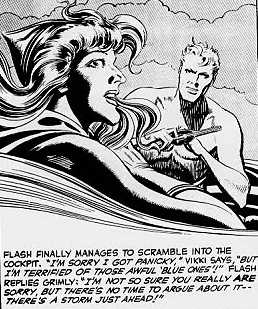

Mac Raboy's Flash Gordon

Mol.1, Dark Horse Comics, 2003

On August 1, 1948, Mac Raboy took over the FLASH GORDON Sunday newspaper strip. Now, Mac Raboy was one of my three favorite comic artists, when I was about 9 years old, for his work on CAPTAIN MARVEL, Jr. For the record, my other two favorites were Jack Cole for his work on PLASTICMAN, and Carl Barks for his incredible duck-work (his name, of course, was unknown to me since he was not permitted to sign his art). Raboy's Fawcett-era artwork was lovely; his academically rendered figures had realistic anatomy, and were drawn in graceful, artistic poses. However, in recent years, I have seen enough of Raboy's original Fawcett art reproduced in publications like ALTER EGO/FCA to be aware of some serious problems. A typical Raboy Captain Marvel, Jr., story contained very little original art; all images of Captain Marvel and whatever villain appeared were photostated from previous stories and pasted in. Raboy and his assistant drew only the barest minimum in the way of characters appearing in that story only, and in the way of backgrounds.

FLASH GORDON, which first appeared as a Sunday strip on

January 7, 1934, featured the dazzling art of Alex Raymond,

which just got better and better as the weeks went by. In

1940 a daily strip drawn by Austin Briggs was introduced.

In 1944, Raymond left FLASH and went on to create a

contemporary "spy action" strip, RIP KIRBY. The daily

strip was cancelled and Briggs did the Sundays until August,

1948 when Mac Raboy took over. A daily strip was not

revived until 1951, with Dan Barry doing the art. Art of

Raymond's calibre did not return to FLASH until EC-great Al

Williamson eventually took over.

This is the first time I

have seen Raboy's version of FLASH, since my local newspaper

did not carry it in the late 40s and early 50s.

This is the first time I

have seen Raboy's version of FLASH, since my local newspaper

did not carry it in the late 40s and early 50s.

A very important transition occurs during Mac Raboy's tenure (with Don Moore writing the adventures). After nearly 15 years, Flash has exhausted almost every possible region of Mongo and is reduced to scouring the many moons of Mongo, such as "Lunita" and the prison moon "Exila," not to mention "the Red Comet," for new adventures. But in the late Fall of 1950, things begin to change. Flash and Zarkov create a "super rocket" and Flash and Dale head back to earth. Things, of course, do not go smoothly, but by April of 1951 Flash and Dale are back on earth, where they help an Einstein-lookalike to construct a rocket to travel to the earth's moon-- and from then on Flash is a trouble-shooting space ace based on earth, having adventures very much along the lines of Buzz Corry, Captain Video and the later Rocky Jones, Space Ranger. By June 1951 Flash is building a space station in earth orbit. Here we first see the teardrop-shaped space helmets that became routine in the strip later, and also in the contemporary Dell comics. Flash soon winds up on Mars (October), then on Rhea, "Saturn's 5th moon" (April 1952), the inside of a comet (September), the silicon-liquid (!) oceans of Venus (October) and back to the earth's moon (March 1953). The last strips in this volume run to April 1953.

Background continuity in these strips is virtually nonexistent. Although Zarkov is left behind on Mongo to run things when Flash and Dale leave, he is with no explanation back on earth to rescue Flash and Dale from various fixes with a giant fleet of space ships. Although Flash builds earth's first space ship, he meets a variety of villains from earth who have been operating on other planets for years, and suddenly interplanetary space is full of passenger liners, isolated colonies of earthmen all over the solar system, and even space pirates piloting flying saucers! When and where Flash and Dale and Zarkov fell into the time warp that brought them to "2350 AD, in the age of the Conquest of Space" is not clear, to say the least!

While Alex Raymond's already good art steadily improved as the weeks went on, Raboy's art steadily deteriorates. I suspect he is using quite a few photostats in his early days on the strip, and Flash, Dale and Zarkov look just the way they should. But their appearances quickly change. Raboy seems to be able to draw only one young female face-- looking vaguely like Mary Marvel-- and with only one (oddly blank) expression. So other females in the strip can be distinguished from Dale only by hair color or style. Eventually, Raboy is reduced to putting futuristic eyeglasses on all female villains to distinguish them from Dale! Flash soon starts looking like a generic (and generally expressionless) blond hero-- nothing like Raymond's Flash. And all villains almost immediately come to look alike; they are invariably bearded, with round faces. Even the little monsters that Flash and Dale encounter on various planets look pretty much alike-- dwarves or gnomes with scaly skin. The same poses are repeated over and over, and it sometimes looks as if inexpert assistants are inking over photostats.

This Dark Horse trade paperback gives you more than 250 9x12 glossy pages, each containing one Sunday strip in sharp, crisp black and white, for a mere $19.95. It's a bargain, and because of the historical importance of Flash Gordon and Mac Raboy, these strips deserved to be preserved, whatever their deficiencies as regards art and scripting. Two or three other volumes are shortly to appear.

Click here for yet more SPACE REVIEWS!